Quarterly Perspective for 2Q24

- Mark Carlton

- Aug 2, 2024

- 8 min read

Summary

The S&P 500 gained 4.3% last quarter, and 15.3% in the first half of the year[1]. That is the good news. The bad news was that this return was driven by a handful of stocks; the market as a whole did not make nearly as much. The Dow Jones Industrial Average declined -1.7% last quarter, and the Russell 2000 Small Cap Index gave back -3.3%. The U.S. stock market has been trading on the premise that the economy is slowly moving toward recession and in that environment only large companies with strong balance sheets and large cash hoards can prosper. There may only be 15-20 companies that qualify, but these companies comprise over 50% of the market capitalization of the S&P 500 index. Oddly enough, we have many days where the top handful of firms move in the opposite direction as the rest of the stock market. More on that later.

Foreign market performance reflects the strength of the U.S. dollar. In local currency terms, foreign markets are up 11% but to U.S. dollar investors (like ourselves) foreign markets are up only 6%. The poorer performance of international stocks in U.S. dollar terms is why we hedge about 30% of our international stock exposure. The dollar has been particularly strong against the Japanese yen, where hedging has improved returns by 15%. In the case of a stronger currency, such as the Indian rupee, the performance difference is only 0.3%. Taiwan has been the strongest foreign market due to one superstock (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company). Brazil has been the worst of the large foreign markets.

Bonds were interesting last quarter. Ostensibly, the bond market returned nothing (0.0%) in the second quarter, leaving year-to-date performance of the Bloomberg US Aggregate benchmark at -0.7%. However, unlike with stocks and the S&P 500, it is comparatively easier to find bonds not in the benchmark that outperform. We use a higher portion of short-term bonds in our portfolios and with the Federal funds rate at 5.37%, these positions returned about 1.3% over the quarter. Our longer-term bond funds tend to have a higher exposure to out-of-benchmark bonds, non-rated bonds, and credit, and these positions earned over 0.5% for the quarter on average. A smaller percentage of bond portfolios were invested in opportunistic public credit or private credit, which generated nearly 2% over the quarter, on average.

Gold returned 3.5% in the second quarter. Hopes for interest rate cuts later in the year and concerns over the rising debt levels in the United States offset the headwind of a strong dollar. Other commodities barely budged. Oil prices continued to be restrained despite the continuing conflict and risks in the Middle East.

[1] JPMorgan 3rd Quarter 2024 Guide to the Markets page 15

Activity

Most of the activity in the second quarter involved trimming or moving money out of what wasn’t working (small and mid-size U.S. stock funds, alternatives in the real estate or global infrastructure areas, and ETFs that focus on out-of-favor niches of the market). I believe the valuations of the largest companies in the S&P 500 are very rich by historical standards. However, I also know we haven’t had such an enduring period of technological domination of the economy before. I want to protect investors from the risks of extreme over-exposure to a sector, but I also need to provide competitive investment performance. The bottom line is that despite my concerns, I have had to increase the weightings of these stocks in portfolios. A strategy of “buy low, sell high” sounds good, but it has not worked well over the last ten years, and it hasn’t worked at all since March 2023. Again, more on that later.

Outlook

So much depends on which comes first: recession or interest rate cuts. If recession comes first, small stock prices are going to stay depressed, and large stock prices are going to converge with them on the downside. If interest rate cuts come first, investors will likely conclude that recession will be largely or completely avoided, and small-cap and value stocks will probably converge with large-cap stocks on the upside. If the worst of the inflation is behind us and the economic future is better, investors don’t need to limit themselves to 15 or 20 names; the vast majority of stocks will do better. The “safety premium” in those large technology names will be reduced because it isn’t needed. The dramatic, colossal outperformance by large tech stocks required an environment of “not too hot, not too cold”. That dovetailed nicely with what the Federal Reserve was trying to achieve (an inflation-reducing slowdown without an actual recession). This environment has already lasted a very long term and produced price distortions of epic proportions. One way or the other, I believe that is near its end.

An aside – yes, this is the Outlook section, but I have no desire to comment on the upcoming election. As the first few weeks of the quarter have shown, the outlook in one week is very different than the outlook in the following week.

Commentary - Buy Low, Sell High Versus Buy High, Sell Higher

It has long been the popular cliché – How do you make money on Wall Street? Buy low and sell high! My training as a financial analyst in the 1990s was all about trying to find undervalued securities and holding them until their value was realized. You didn’t chase the market – everybody knew that didn’t work. Mountains of studies were undertaken going back to the late 1920s and all of them concluded that finding a good company at a fair price and patiently holding that stock and collecting the dividend was the key to wealth accumulation. If that wasn’t enough, you had the Oracle of Omaha, Warren Buffett, admonishing the speculators and preaching discipline and patience. After all, you didn’t want to be like those speculators of the 1920s who wound up jumping out of windows when the market crashed or those who were wiped out when the Nifty Fifty craze ran smack into the Arab Oil Embargo in 1973.

As is often the problem with things we all know to be true, market certainties can cease being true. Buy high, sell higher is the competing strategy with "buy low, sell high.” It argues that the best way to make money is to buy stocks that are already doing well, because those companies are more likely to continue to do well. It offers the psychological advantage of buying winners that the other strategy does not. Value advocates had claimed, with apparently good reason, that the market doesn’t reward you for doing what is easy, or else every investor would be rich.

Starting about 10-15 years ago, things began to change. “Buy high, sell higher” began performing a lot better than a value-oriented strategy. Some of us market veterans believed that this outperformance was a cyclical anomaly and that in a few years the stock market would go back to behaving as it always had. Sometimes markets get a little frothy, but they always self-correct. We thought this would happen in late 2018 as higher rates caused a bit of a hiccup, but in 2019 the new paradigm re-asserted itself. We thought it again in 2020 after the sharp Covid plunge and again in 2022 with the inflation surge, but each time the most loved, most expensive stocks lapped the rest of the field. So much so that studies from 1946 to the present show that “buy high, sell higher” is a superior strategy. It seems that omitting the Depression Era is significant because surviving stocks had a very large bounce after the worst of the Depression passed which skewed the numbers. In any event, outside of a smashing of the stock market, momentum contributes positively to investment returns over the long term versus value. The question is, what do you do with this information now?

The easy answer would seem to be: “buy high and sell higher.” The data shows that the strategy works and it is certainly ingrained among stock investors today. When I started in the industry 37 years ago there was nothing that excited investors more than a stock that was trading for less than book value.[2] It was like finding money on the street. Today nobody looks at book value. It might take years to realize that hidden value, whereas a hot stock can make you good money in an hour or two. But even if you accept the premise that “buy high, sell higher” is a superior strategy, you have to believe that 1) there is no new Depression coming; and 2) that the current period isn’t a distorting anomaly in the opposite direction of what the Depression Era was.

I recently attended a presentation on the current state of buy low, sell high (value) investing. The subtext was: “why isn’t it working anymore?” Of course, that was the wrong question to ask. The right question is: “why is buy high, sell higher (growth) investing doing so well?” The reason is that growth previously consisted of companies and industries for which their advantage was transitory. Falling commodity prices helped consumer and food stocks in the 1980s, but eventually, commodity prices leveled out. The pharmaceutical companies were the growth winners of the early 1990s, but over time expiring patents and regulatory scrutiny over price gouging caught up with them. We all know about the late 1990s dot.com boom and bust and the early 2000s banking and real estate rise and hard fall. The market was dynamic, and no company or industry stayed on top for more than a few years. If you bought high, chances are you bought close to the top and things didn’t work out all that well for you. Then came the platform technology companies.

By platform, I mean that the company was able to create its own ecosystem. You bought the product (iPhone, Tesla, etc.), and you were locked into paying for its services and upgrades. You used the service (Amazon, Google, Facebook) and their related applications made it difficult to go elsewhere. Nobody could effectively compete. There are streaming alternatives to Netflix and semiconductor chip alternatives to Nvidia, but right now they are not nearly as good. Platform companies command relative valuation levels today that are larger than the best companies of the last century could dream of. Maybe this is justified. But only if the world stops changing.

[2] “Book value” meaning the current market value of a company’s assets minus it’s liabilities.

Some Charts of Interest

This is a chart of active management versus passive (index) management. What it shows is that it has been very difficult for active managers to beat the over the past ten years because the biggest stocks have done so much better than large stocks as a whole. When you go to mid-size and smaller stocks, you don’t find dominance by a few stocks and as a result managers beat indexes a greater percentage of the time.

There are some concern that inflationary cycles have two waves. The Federal Reserve has been reluctant to cut rates as the Fed did in the 1970s lest they get a similar result.

Investors seem to be “all-in” for stocks right now. Current levels of loving stocks and hating bonds are reminiscent of past cycles, each of which preceded a decade or more of stock weakness.

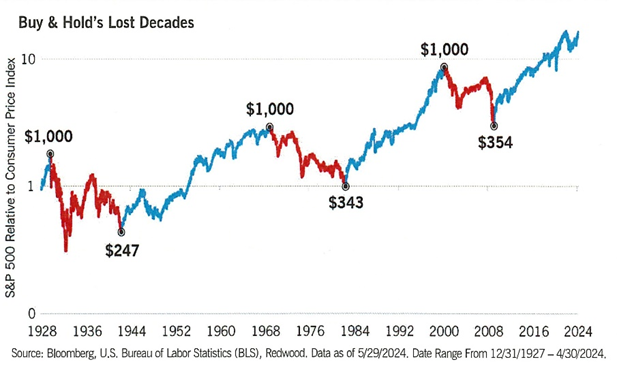

Following the previous chart, once a long-term uptrend ends (and I’m not saying we are at that point yet) investors have to be very creative in order to maintain purchasing power.

Comments